The Maine Grain Alliance Presents

Kids Grain Education

Grains are everywhere! We hope that you enjoy learning about grains and have a new appreciation for what goes into your sandwich bread, your cereal bowl, and your macaroni and cheese!

Imagine sitting down to a nice summery meal that includes corn on the cob, tomatoes, and cucumbers. Yum! And we bet that you can picture where and how they grow and maybe even some of you have planted them and harvested them as well! But where does that bread come from that is on the table? Or the pasta salad? Or for that matter, the cereal or oatmeal in your bowl in the morning?

Does bread grow on a stalk like corn?

Are there little pasta vines that run along the ground?

Do Cheerios hang from a short plant?

Bread, Pasta & Cereal Grains

We, in Maine, are not as familiar with what grains look like in the fields, because in Central and Southern Maine, most of the fields are covered with hay or corn. But a trip to Northern Maine will start to tell a new story.

Maine used to provide a lot of grain to New England, but thanks to the Erie Canal and pricing, the business of grain growing moved to the midwestern part of the United States, where you can picture thousands of acres of grain. But, over the past 5-10 years, Maine’s farms have been growing more grain, as seen in the picture above. Grains are important rotational crops that keep the soil healthy. The demand for organic grains is growing rapidly as well. The Maine Grain Alliance is working with farmers across Maine to help restore some of the heritage grains to our soil and to help improve the economy of Maine.

Farmers in Aroostook County are growing grains in rotation with potatoes. Crop rotation improves the soil and now that there is a market for grain, it makes good financial sense too. Here, you can see wheat fields in the back and potatoes in the front.

Potatoes & Grain in Maine

Farmers in Aroostook County are growing grains in rotation with potatoes. Crop rotation improves the soil and now that there is a market for grain, it makes good financial sense too. Here, you can see wheat fields in the back and potatoes in the front.

Photo courtesy of University of Maine Extension Service

Teachers:

The Maine Grain Alliance is offering individualized one cup baggies of pancake mix, created in a Covid-approved commercial kitchen, with ingredients and instructions attached. We can also provide individualized stalks of grain as well as small packages of seeds (corn or wheat) to be grown in test plots.

Please contact Kayla Starr, Maine Grain Alliance Program Director, at kayla@mainegrainalliance.com for more information. We welcome comments as well.

Furthermore, the website Maine Ag in the Classroom is a terrific resource.

Learn All About Grain

Learn how grain is grown, harvested, milled, and used!

Growing Grains

Explore how barley, oats, flint corn, wheat, and more are grown in the Northeast!

Harvesting Grain

Understand how grain is taken from the stalk, chaff seperated, and how it is stored.

Milling Grain

Grain is made into flour by the process of milling. In Maine, we use stone mills!

Using Grain

So many deleicious treats are made from grain including bread, cookies, pasta, and more!

Baking Videos Led By Kids

Making Pancakes

Baking A Bread Boule

Baking Brazilian Cornmeal Cookies

Sourdough Rye Crackers from Maine Grains

Visit the Maine Grains website for super fun sourdough rye cracker recipe and short video!

Explore Fun Activities!

Learn about important grain places in maine!

Find Aroostook County, Linneus, Skowhegan

What is important about each of those places?

Grain Math Problems

Fun with numbers

- One bushel of wheat produces 42# of flour. There are 65 bushels in an acre How many pounds of flour are produced in an acre?

- If a loaf of bread requires 1.5 pounds of flour, how many loaves could be produced in an acre?

- If a family eats 3 loaves of bread every week, how many weeks would it take to eat all of the loaves from that one acre?

- A loaf of bread requires 1.5 pounds of flour. If your family eats three loaves of bread a week, how many pounds of flour would you need in a year? If you buy that flour in 5 pound bags, how many bags of flour would you need to buy?

- A recipe for bread calls for 4 cups of flour, 1 pint of water, 2 tablespoons of yeast, and 1 teaspoon of salt.

- How much of each ingredient is needed for 2 batches of bread?

- How much of each ingredient is needed for 3 batches of bread?

Learn How to Draw Wheat

Grain Coloring Sheets!

Special thanks to Uproot Pie Co. for making these for us!

Grain Growing

When we talk about grain, we often only think about wheat, the type of grain that is made into flour for bread, pasta, cake, pizza dough! But there are many different types of grain grown in Maine, and there are more and more grain species being developed and tested for success in Maine.

One of these grains is OATS, and you eat them in oatmeal and oatmeal cookies!

Oats belong in the grass family Oats are a cereal grain from the grass family, and are used as food for both humans and livestock. The plant has slender stalks that can grow up to four feet high. The stalk ends in spikelets that contain flowers from which a husk-covered seed develops. There are approximately 25 species of oats, most of which grow in cool, moist regions of the world (temperate regions) such as Maine. Oats even grow well in poor soils. Some species are cultivated for their grain (for human consumption as cereal and as feed for cattle and horses), some are grown for the green stems and leaves (for hay, silage and pasture), and some are cultivated for dry straw (bedding for livestock), and for covering crops such as strawberries during the winter. Oats are an important rotation crop on livestock, grain, and potato farms in the northern United States, Canada and parts of Europe. In Maine, oats are mainly grown in Aroostook County, with a small amount grown in central Maine. They are grown primarily as a rotation crop with potatoes and are used as grain for animal feed. The crops are planted in the spring and harvested in mid to late summer. In 1997, 23,000 acres of oats were harvested in Maine. Find oat harvest for 2019 In the spring, oat farmers hook up a plow behind their tractors and drive them back and forth across the fields. The plow digs down about 6 to 8 inches and turns the soil. This helps break up the soil so it will be easier for planting. Next, a disc is pulled behind the tractor over the soil. The disc is made up of about 25 round metal blades, each about the size of a Frisbee. This cuts the soil up into small pieces so the field doesn’t have any big clods that oats won’t grow so well in. Then they plant the oat seed with something called a grain drill. They pull the grain drill behind a tractor. The grain drill opens up a little slit in the soil and drops in oat seeds. Then it closes the slit and presses the soil around the seed. Oat seeds are a little bit smaller than an apple seed. The oat seeds are usually planted in May. The next important ingredients for growing oats are provided by Mother Nature herself, with rain and sunshine.

Another grain is FLINT CORN. This is an important grain that is used in cornmeal and polenta and was a very important crop to the Native Americans living in our area.

Flint corn is a different crop and experience entirely from the traditional summer sweet corn.

Flint corn is a different crop and experience entirely from the traditional summer sweet corn.

Known most commonly in the modern era as the colored stalks of dried corn that pop up around Thanksgiving, flint corn played a much more integral role centuries ago, serving as the the staple crop in Native American cultures across the Americas. Each region had its own varieties of flint corn that had adapted for growing in the area’s climate.

With a harder external shell on its kernels than sweet corn, flint corn is most commonly ground into cornmeal and serves as the basis for traditional foods such as corn tortillas, porridges and cornbread.

In Maine, and other colder Northeastern states, flint corn varieties that could mature in a shorter growing season were the strains that prevailed historically. However, as commercialization took hold on agriculture, the prevalence of flint corn diminished.

“Flint corn would have been a staple of, not just Maine Native American diets, but it would have been a staple of all farm diets in the 1800s,” Barden said. “The shift was made away from flint corn because you could get more production, more volume per acre, from different kinds of corn. It was a shift, I think, from everyone taking care of their own needs to it becoming more of an industrial commodity kind of thing.” (article on Albie Barden’s work to restore flint corn, Bangor Daily News 4.24.2017)

Another important grain is WHEAT and this has perhaps the most varied of uses that you are familiar with.

Somerset County in Maine was at one time the breadbasket of New England, producing 239,000 bushels of wheat per year at its peak in 1837, enough to feed more than 100,000 people. When the Erie Canal was built, it was easy to get the less expensive grain from the midwest to New England and the grain growing in Maine began to die out. But, there has been increased interest in growing grain in Maine, especially organic varieties, and the Maine Grain Alliance, the University of Maine, and farmers in Maine have been working together to understand the varieties that will grow here successfully. With a combined effort, there is now commercial production of a heritage wheat from Estonia, along with several other heritage varieties.

There are hundreds of varieties of wheat grown in the United States, but they are grouped into six classes based on hardness, color, and the time of year they were planted. The six classes of wheat are: hard red spring, hard red winter, hard white, soft red winter, soft white, and durum. Millers and bakers need to know what class of wheat they are using, because each type of wheat makes a different type of flour and is used in different types of foods. Hard wheat varieties are used to make breads and rolls. The soft wheat varieties are used in cakes, cereals, pastries, and crackers. Durum, the hardest wheat of all is used in pasta, macaroni, spaghetti, lasagna, and more. Hard red spring wheat has the most protein. It is usually blended with other classes of wheat to make all-purpose flour.

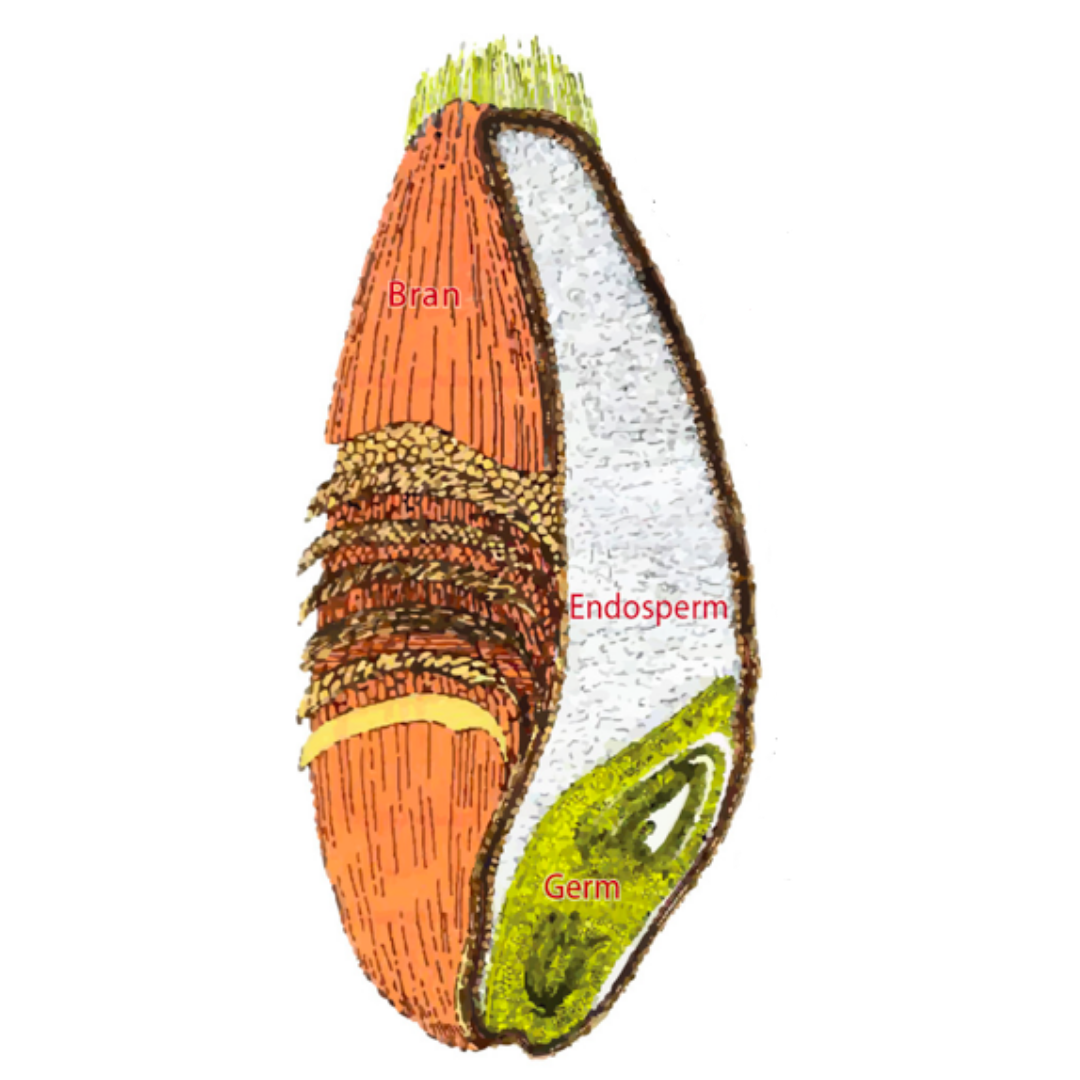

Wheat kernels are tiny, even smaller than our little fingernails! There are about 50 kernels in a head of wheat and 15,000 to 17,000 kernels in just one pound. The larger inner portion of the kernel is called the endosperm. It is the part that is ground to make white flour. The hard outer coating is the bran, sometimes used in cereals, muffins, and breads. This portion is made of many layers. Finally, the tiniest part of the kernel is the germ. It is the part that grows into a new wheat plant if the kernel is planted in the soil. Whole-wheat flour is made when the whole kernel is ground or milled. Whole-wheat flour contains all three parts of the kernel

Warm moist days make the wheat plants grow quickly. They usually grow to be 2 to 4 feet tall. A wheat plant has four basic parts: head, stem, leaves, and roots. The head contains the kernels. The stem supports the head. The leaves conduct photosynthesis and the roots hold the plant in the soil. (excerpts from Nebraskawheat.com)

There are other varieties of grain grown in Maine: Rye, Barley, and a seed called Buckwheat.

Once the grain is fully grown and relatively dry, it needs to be harvested.

Grain Harvesting

How do farmers know when the wheat is “just right” for harvest? Many farmers take a sample of wheat to be tested to see if it is dry enough to harvest. Other farmers check their wheat the “old-fashioned” way. They rub the wheat head in their hands, blow away the chaff, or the straw like outer covering of the kernel, and chew some of the grain. If the kernels are hard and make a gummy substance as they are chewed the farmers know the wheat is ready to be cut. Here in Maine, winter wheat is harvested mid summer, while spring wheat, corn, and oats are harvested in the fall. Wheat is harvested with a giant machine called a combine. It cuts, separates, and cleans grain all at the same time. Before the combine was invented, farmers had to use two separate machines for harvest- a reaper, or binder, to cut the grain and a threshing machine to separate the kernels from the chaff and stems. The combine got its name, because it “combines” the jobs of both machines. (from Nebraskawheat.com) Grains are then stored in silos before they go to the mills for processing.

Smaller plots of grains are harvested with small harvesters and cleaned with (Richard, please add some detail here) Often, these smaller plots are test plots where the grower can determine if the grain will grow in Maine. The seeds from the successful plants are then kept and replanted the following year. This is called the “growing out” process and the goal is to have commercial amounts of the grain available for large acreage.

Milling Grains

There are two stone ground mills in Maine: Aurora Mills in Linneus and Maine Grains in Skowhegan. Grain drops into the middle of two stones and one of the stones grinds the grain into flour which then flows out of the side of the stone and is captured and stored and then bagged for market. There are many different products that are produced at these mills: cornmeal, corn flour, and polenta from corn; oat groats, cracked oats, and rolled oats from oats; various products from wheat, rye, and barley.

Stone milling allows for all of the important parts of all grains to be captured for nutrition. Here is a wheat kernel, or seed. It is enlarged so you can see how complex one kernel is. Kernels are very tiny even smaller than our little fingernails! There are about 50 kernels in a head of wheat and 15,000 to 17,000 kernels in just one pound. The larger inner portion of the kernel is called the endosperm. It is the part that is ground to make white flour. The hard outer coating is the bran, sometimes used in cereals, muffins, and breads. This portion is made of many layers. Finally, the tiniest part of the kernel is the germ. It is the part that grows into a new wheat plant if the kernel is planted in the soil. Whole-wheat flour is made when the whole kernel is ground or milled. Whole-wheat flour contains all three parts of the kernel

Using Grains

We most often think of oats as a breakfast food. But oat groats can be used in place of rice and there are lots of imaginative ways to include it in your meals, in breads, and cookies. Flint corn makes delicious cornbread, johnnycakes, polenta, and can be added to all sorts of items that you might think are typically wheat-based, like bread, cookies, pie crust. You only need to use your imagination. Wheat and Rye are often used for baking bread, but they can be used for pastries, and the berries themselves also can be used in place of rice and pasta. Truth is, all of these grains can take the place of the white flour that so many of us imagine when we think of baked goods. Try different grains!