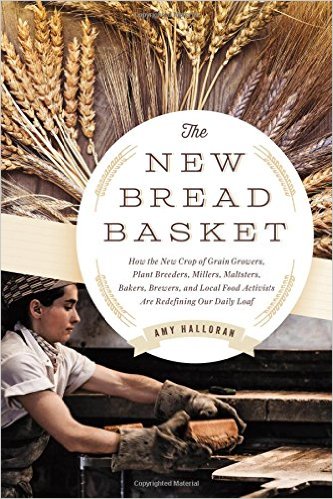

This excerpt is adapted from Amy Halloran’s The New Bread Basket (August 2015) and is printed with permission from Chelsea Green Publishing.

Every July, people come to central Maine to learn about breads and grain. The Kneading Conference takes over the Skowhegan Fairgrounds and makes a little world where everybody speaks some tongue of bread, fire, or flour.

The fair is old but the grandstand is new, and looks like the long mouth of an aluminum giant. This is the first thing you see when you park, and there’s no hint that, behind the grandstand, the stage is set for bread. Rolling racks of sheet trays prop up long-handled peels made of steel and wood. Stacks of bowls wait on tables beside plastic tubs for proofing dough. Piles of bricks are ready for a masonry oven workshop. Bags of sand and mortar will become the mud hump of an earthen oven.

The fair is old but the grandstand is new, and looks like the long mouth of an aluminum giant. This is the first thing you see when you park, and there’s no hint that, behind the grandstand, the stage is set for bread. Rolling racks of sheet trays prop up long-handled peels made of steel and wood. Stacks of bowls wait on tables beside plastic tubs for proofing dough. Piles of bricks are ready for a masonry oven workshop. Bags of sand and mortar will become the mud hump of an earthen oven.

Mornings are misty and chimneys puff smoke from ovens that look like mushroom caps, lending a hobbity feel. People eat meals together at long picnic tables, granola made from local oats, and loaves from the day’s classes.

For two days, people make tough choices about compelling workshops: baking with rye, or using sprouted flours? The story of grain projects in the Northeast, or Arizona? Baking teacher all-stars sit in on one another’s classes like jazz musicians at a club, weighing in on questions of fermentation and timing. Serious home bakers come to perfect their hearth-style artisan loaves or laminated doughs. Professional bakers come to learn, too.

On the third day, bakers make their slow good-byes and the Artisan Bread Fair draws big crowds. People eat pizza from a wood-fired oven and take home interesting loaves. Vendors sell Maine kelp and hand-loomed scarves. These booths have little to do with the conference’s topic, but relate to its gut message of reviving local economies.

Snug in the midst of lakes and woods, Skowhegan is home to eight thousand people. The former mill town wraps around the banks of the Kennebec River and its dammed falls. From the 1830s to the 1950s, people made things here and jobs were plentiful. Now the paper plant and the hospital are the prime employers, and 51 percent of the county qualifies for federal food assistance.

Author Richard Russo knows this kind of place, and so do I. He grew up not far from me in Gloversville, New York. Early in the twentieth century, my city of Troy made 90 percent of the world’s collars and cuffs, and Gloversville made most of the gloves. Instead of using his hometown’s particulars to explore blue-collar life, he used Skowhegan and neighboring towns to model the worn-out mill town that starred in his book Empire Falls. The 2001 novel won the Pulitzer Prize, and the movie was filmed in and around Skowhegan. Exemplifying the wasteland of the postindustrial Northeast wasn’t the kind of notoriety everyone wanted. Some people decided to rewrite the narrative of Skowhegan, not on the big screen, but on the more lasting screen of everyday life.

“We needed something new to be known for,” said Amber Lambke, who directs the Maine Grain Alliance and a slew of projects to revitalize grain production. Initially the community’s revisioning efforts were aimed at beefing up the economy in general. In 2005, the town began participating in the Main Street Program, a national strategy to help struggling downtowns bolster themselves. They started a farmers market. Amber was volunteering on these initiatives when she and her neighbors came together to discuss other possible steps.

These neighbors included a fair number of bakers and masons. Albie Barden had an idea. Albie builds ovens and is the Johnny Appleseed of masonry heaters, a style of radiant heating that relies on collecting warmth from intense fires in bulky masonry structures. He’d recently spoken at Camp Bread, the Bread Bakers Guild of America’s immersion workshop, and at another bread gathering hosted by Alan Scott, whose ovens and oven plans helped launch the artisan bread movement in the 1990s. Alan Scott suggested Albie organize an oven and bread conference on the East Coast.

Decades before, Albie helped start the Common Ground Fair. This is MOFGA’s (the Maine Organic Farmers and Gardeners Association) harvest festival and draws fifty thousand people each September to celebrate handmade living and share the necessary tools and skills. The Kneading Conference could be a similar celebration and skill-share event based on bread and grains.

The topic seemed a perfect magnet. The artisan bread movement had sparked a need for baking instruction and a demand for wood-fired bread and pizza ovens. Bakeries from as far away as Boston were hunting for local flour. Over the course of six quick months, organizers mapped out a two-day plan, inviting experts to speak about their work in the field and teach baking classes. Don Lewis, whose Wild Hive Bakery had built a regional grain and mill project in the Hudson Valley, would be the keynote speaker.

In the summer of 2007, the first Kneading Conference drew seventy-five people to a church parking lot. Three years later, the event moved to the fairgrounds, which proved a good spot to stitch bread back to the land.